Whatever Dallas’s physician talent capitalization rate is, it is obviously not as high as it can be. When we identify football talent we send kids to football camps, invest in private coaching, and the entire community starts pulling for the kid’s success. What if we applied the same level of nurturing to a child that shows promise to become a physician? The impending physician shortage is an issue that we must address—not only from a nationwide perspective but locally in Dallas as well.

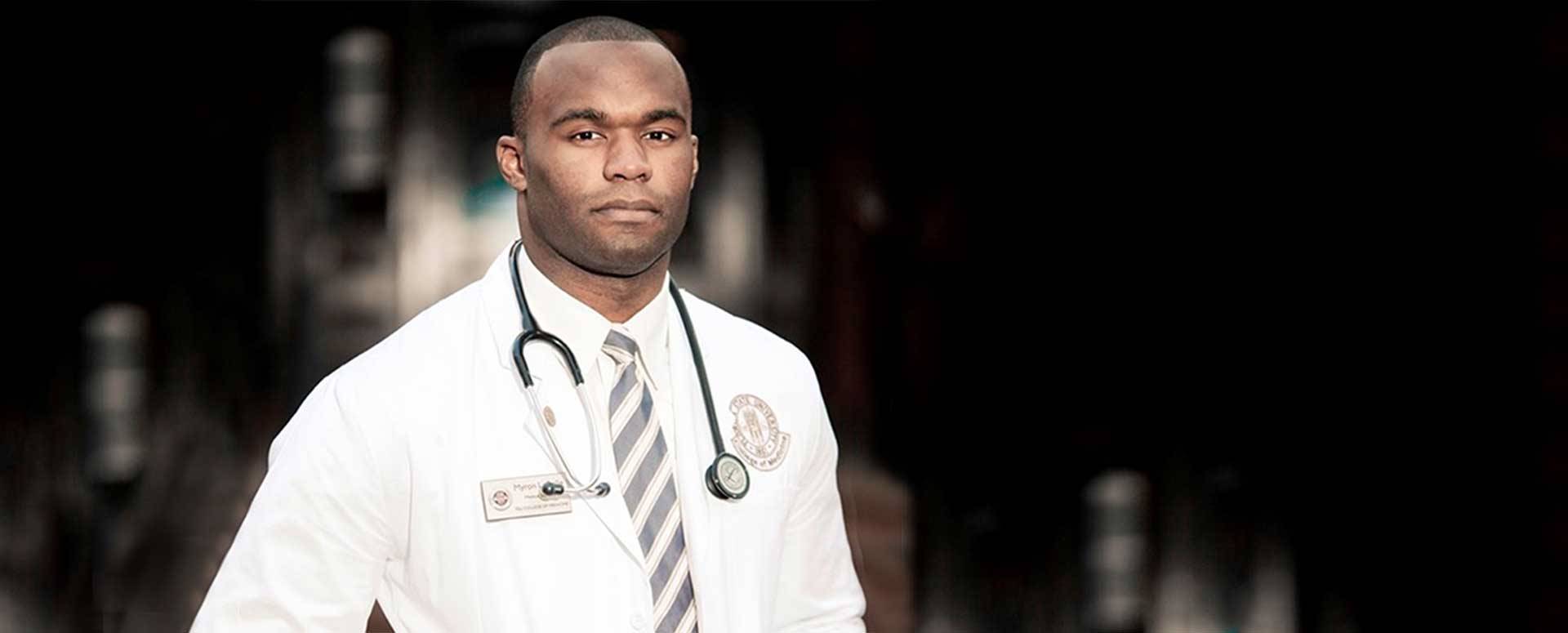

I have been working with Dale Okorodudu, MD, and Thomas Bennett, MBA to host a

Black Men in White Coats Youth Summit on the campus of UT Southwestern Medical Center on February 16th. We are expecting over 1000 students (boys and girls third grade and above) to be in attendance. The Summit will provide inspiration and mentorship to DFW’s youth who are interested in healthcare as a profession. Throughout the day, students will engage in hands-on activities and network with healthcare professionals from diverse backgrounds. The goal is to inspire and show them that there are people who look like them in the medical field, and if others like them have done it, then so can they. The Summit will also provide tangible information to educators, parents and community leaders to inform them of what they can do to help nurture our physician potential.

We cannot afford to only select from a small demographic. We must ensure that regardless of socioeconomic status, ethnicity, or geographic location, we find all of the existing talent, harness and develop it. This is not something that can be accomplished by solely relying on physicians of color. There are simply not enough Dr. Dales to go around. This is a job for all of us.

“We have a scarcity of achievement in this country, not because we have a scarcity of talent but because we are squandering talent. This is good news…because that means we can do something about it.”

So let’s do something about it. It takes a village. So let’s be the village.

More information about the Black Men in White Coats can be found at www.blackmeninwhitecoats.org